Onasis I is, quite simply, wonderful. Onasis II, not so much, but it’s very listenable all the same, as long as you’re not seeking the depth and emotion of his previous records. I like to listen to this record whilst ironing.

Onasis I is, quite simply, wonderful. Onasis II, not so much, but it’s very listenable all the same, as long as you’re not seeking the depth and emotion of his previous records. I like to listen to this record whilst ironing.

Richard Swift: An appreciation

In the past 22 years I’ve tried on more music than I’ve had hot dinners. When I was 3 I decided I wanted to be Kylie Minogue, but thankfully, I soon got over that. At 16 it seemed like a good idea to cut my hair wonky and listen to the Clash (not my wisest move). And my university years were played out to a cacophony of awful, soulless “indie”, which my peers revered and I detested. It was only when I came to realise that I wanted music with substance, like a woolly jumper of potent melodies and intelligent lyrics knitted intricately together, that I actually found it.

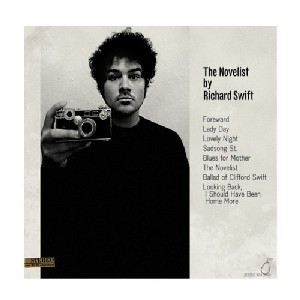

In 2005, Secretly Canadian reissued the first two records of a curly haired chap called Richard Swift as a double-album, entitled The Richard Swift Collection, Vol. 1. This rather understated labelling replaces the previous titles of The Novelist and Walking Without Effort. Whilst cynicism would lead one to presume that this is a clever ploy by the record company to draw attention to two relatively unknown records in one fell swoop, the pairing of the two actually works remarkably well. The main contrast between the two discs is their sound; whilst The Novelist has a cloudy, almost sepia-tinted quality to the recordings (although never allowing itself to sound like a shoddy, home-made effort), Walking Without Effort is altogether clearer and fresher. What binds the records so inextricably is the wistfulness that shrouds each of the tracks, which individually emanate a yearning for times passed, or perhaps times that never even existed.

Undeniably the more distinctive record of the two, The Novelist channels the nostalgia of the collection through expressions of personal sadness; a factor which is most heartbreakingly evident in Sadsong St and the title track. The opening line to the latter, “I am New York / tired and weak / I try to write a book each time I speak”, is sung with immense gravity and perfectly encapsulates the helplessness and resignation that Swift expresses in The Novelist, either at his role as a ‘troubled’ artist, or at the passing of time. The closing track of the record, Looking Back, I Should Have Been Home More, is so heavily loaded with regret, that the passing into Walking Without Effort is almost a tangible experience of immense weight being lifted from the listener’s heart.

Listening to Walking Without Effort as a record is far more upbeat and optimistic than it’s predecessor, and the last few crumbs of wistfulness remain only in the use of similar pre-rock instruments rather than in the subject matter. Juxtaposing the sorrow of The Novelist with the optimism of Walking Without Effort actually plays to the strengths of both records. The stand-out track amongst the last collection of songs is the cheery As I Go. Much like Losing Sleep and Beautifulheart, this song emits the warmth of redemption through love, exploding into the chorus of “If I falter / If I fade / You will hold me still so close”.

Such a short analysis cannot, I feel, do justice to The Richard Swift Collection, Vol. 1. If it seems that this collection is a straightforward sadness/happiness split then I have fumblingly misled you, as there are various cross-over points in the two records. For example, Losing Sleep and Mexico (1977) are certainly reminiscent of the anxious sensitivity from The Novelist’s title track. What is so refreshing about Richard Swift amongst so many other songwriters of present day is that his music is loaded with depth and texture, and it seems that the Swift records that I listen to currently are completely unlike the music I heard upon my initial listen in 2005. Even now, I find myself constantly surprised by Swift’s artistry and small details that I hadn’t previously noticed in his music. Furthermore, Richard Swift possesses the ability to conjure a plethora of images from various points of my experience. Similarly, objects and memories can evoke strands or even whole songs of Swift’s music in my mind, such as an antiques market, a black and white photo, or the smell of an old pipe. In The Novelist and Walking Without Effort, Swift has composed a soundtrack to a lost time, but leaves this time open to the listener to fill with their own memories and ideals. And this is what makes The Richard Swift Collection, Vol. 1 so universally appealing.

Following such a debut was undoubtedly going to present Swift with quite a task. I faithlessly doubted that he would be able to produce a record as fine, and believed that Richard Swift would be struck down with “second”-album-syndrome and create an offering which was a mere dilution of his first. Predictably, and delightfully, I was wrong.

Although wholly more upbeat than it’s predecessor, Dressed Up From the Letdown deals with the transition between The Richard Swift Collection, Vol. 1 and itself easily and knowingly. The opening track, the album’s namesake, seems to resist drawing attention to itself, preferring instead to slowly increase it’s presence by the progressive layering of echoey vocals, soft and steady hand claps and whispery guitars. The title itself speaks of disappointment and loss, but in comparison to The Richard Swift Collection, Vol. 1, there is a shift in the material’s focus from reminiscence over times past to looking into the future. This progression is echoed further on in the record with the introduction of a solitary, steady trumpet which pre-empts the buoyant tone running throughout Dressed Up…

The title song leads perfectly into the album’s second track, The Songs of National Freedom, which shakes off the cobwebs of Swift’s previous work and leads the listener into an optimistic frolic of the “oom-pa-pa” variety. After continuing this sense of exhilaration in Most of What I Know (punctuated by the rejoicing cry of “your love will keep my heart alive”), Swift then introduces the secondary theme in the record. Buildings in America and Artist and Repertoire introduce Richard Swift the downtrodden and often self-deprecating artist. The sigh of “I played your heart but I broke two strings” presents a Swift who regards himself as clumsy, undeserving and lacking in grace, a sentiment which is echoed in Artist and Repertoire’s representation of the callousness of a record industry which casts aside sincere and uncontrived music. The opening line "Sorry Mr. Swift, but there’s no radio that likes to play the songs of your lovers’ sorrow", paves the way for a painful and heart-rending account of a conversation between Swift and an A&R man, leading to the humiliating “Sorry Mr, Swift, but you’re much too fat and could I persuade you just to wear a cap?”. In recounting this, however, Swift displays the resilience of an artist who firmly grasps the tribulations and criticisms facing artists in the record industry, transforming them into an artful show of defiance, which echoes The Songs of National Freedom’s declaration of “I made my way into the spotlight / just to realize it’s not what I want”.

Following this tale of disillusionment, the tempo picks up yet again for the marvellously upbeat Kisses for the Misses and P.S. It All Falls Down, both of which cloak knowing attacks on the temporality of success and false friendships in jubilant, jazz-like piano plinks and plonks.

The album closes just as subtly as it began, slipping out via The Million Dollar Baby’s convoluted but heartbreaking sentiment of “I wish I was dead most of the time / but I don’t really mean it”, into the folky, unobtrusive The Opening Band. Fading into silence, the latter is rather troubling as the collection of songs which immediately precede it can only cause the impression that this fading away is a signifier of Swift’s despair or submission to his self-deprecating impulses. In fact, the low, soft declaration that “we all die when it’s our time” creates the urge to reach out to Swift and pour upon him gratitude and assurances that now is not the time to abandon his art.

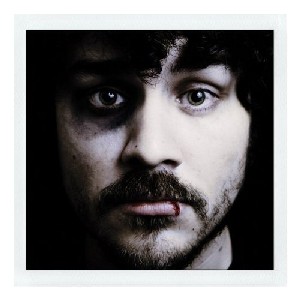

A year later, Swift has returned, still possessing the power to turn his hand to a wide range of musical genres. The artwork on his third release on Secretly Canadian, Richard Swift as Onasis I & II, portrays a weathered and bruised artist who stares out at the listener with wisdom and clarity. Indeed, the main notion created by Onasis I & II is that Swift has overcome his anxieties and self doubt of the previous two records and has returned with absolutely no intention of giving a damn.

Whereas in the past Swift appears to be compelled to speak the truth, it seems that some sudden epiphany has pushed him away from the emotive and honest lyrics he has made a name for himself with, often shunning lyrics altogether. Indeed, Onasis I opens with a 3 minute, instrumental blues romp, pre-empting the remainder of the album in its fuzzy distortion and ‘50s-esque riffs which make toe-tapping impossible to resist.

In total honesty, Onasis I& II is not, in my opinion, his most accomplished work. In fact, until today, my two main opinions were that: a) Swift should have reduced it to one CD, and b) it is difficult to distinguish between tracks because they all sound quite similar. However, Swift’s ability to reveal more depth upon each listen has finally enabled me to see the distinction between each track. Onasis I is, quite simply, wonderful. Onasis II, not so much, but it’s very listenable all the same, as long as you’re not seeking the depth and emotion of his previous records. I like to listen to this record whilst ironing.

Reaching back into the past, much like his earliest work, Swift pulls out a faint, foggy Wurlitzer in Opt I and Du(M)B I. The beauty of this sound lies in its ability to mean so many different things. To some, it evokes fairgrounds and childhood, whereas to me, it has a sinister feel laced with mockery and despair. This is particularly exaggerated when preceded by the buoyant and carefree primitive rock of Knee High Boogie Blues and The German (Something Came Up).

Onasis II’s finest point is undoubtedly the uplifting Dutch which encompasses country, blues and garage rock in sixty four seconds before slipping away lightly. The rest of this second disc is slightly lost on me, as at times it appears to be a repetition of the first. Whilst repetition often unifies a piece of work, Swift doesn’t really add anything to the album by doing this. Herein lies the record’s weakness.

However, what Swift must be commended on is the fact that he does not rest upon his previous achievements and regurgitate his prior successes. Each of his three (or four if I’m being pedantic) albums is entirely unique and bound to upturn expectations, yet they also follow the same trajectory into the past. Richard Swift is an intrepid explorer into a lost time and place, and I for one am highly appreciative of the treasures that he brings back.

Words: Kate Dickinson