"You’ve sang Shang-a-Lang, with your trousers half way up your leg, hung posters of Donny on your wall and kissed the David Cassidy transfer on your pillow at every bedtime. You’ve dressed up in your mum’s high heels, and draping your socks around your neck in lieu of a feather boa, waggled in front of your bedroom mirror to the tinny sounds of Bolan and Gary Glitter in your head. But this is it. "

"You’ve sang Shang-a-Lang, with your trousers half way up your leg, hung posters of Donny on your wall and kissed the David Cassidy transfer on your pillow at every bedtime. You’ve dressed up in your mum’s high heels, and draping your socks around your neck in lieu of a feather boa, waggled in front of your bedroom mirror to the tinny sounds of Bolan and Gary Glitter in your head. But this is it. "

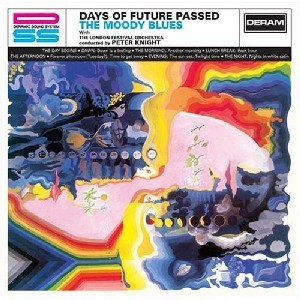

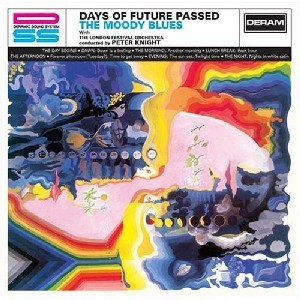

Why Aren’t You Listening? The Moody Blues – Days of Future Passed

Picture this: 1978; another boring weekend at your Grandparents’ caravan in the wilds of Northumbria. You’re in bed, half-listening to Jimmy Saville on the radio, while the bacon for your mid-morning sandwich spits in the pan.

And then you hear it. A plaintive voice, chock full of the heartache of lost love, as it twists and turns against the crescendo of rock band and orchestra, before giving way to the haunting strains of a lone flute rising and falling, then rising again, as though echoing the inner turmoil of the lovelorn singer. You’ve never heard anything like it before, as you jump out of bed, and turn the radio up. For once your mother, raised on a diet of Conway Twitty and Elvis, and whose interest in popular music seems to have hung up its dancing feet at the stroke of midnight 1960, knows the answer to Jimmy’s question. The song is Nights in White Satin; the band, The Moody Blues.

There can’t be many people who can say that their musical taste was formed by the Sunday morning playlists of Jimmy Saville, or at least, not many who would publicly admit to it, but you’re hooked. You’ve only ever listened to music as a kid, lapping up the post-glam era manufactured pop fodder every Thursday night on Top of the Pops. You’ve sang Shang-a-Lang, with your trousers half way up your leg, hung posters of Donny on your wall and kissed the David Cassidy transfer on your pillow at every bedtime. You’ve dressed up in your mum’s high heels, and draping your socks around your neck in lieu of a feather boa, waggled in front of your bedroom mirror to the tinny sounds of Bolan and Gary Glitter in your head. But this is it.

This is the real thing. This song touches you in a way that the recent deluge of post punk new wave scenesters just can’t. You might shuffle in your best sub-teenage boy enticing manner, as read in your second-hand Jackie annual, to Blondie and The Boomtown Rats at the Saturday church youth club disco but your heart isn’t in it. They’re not for you, these skinny, drainpipe clad young men and two-toned haired women. You still hanker for your flares and wedges, and songs that last longer than an explosive three minutes. You’re ready for something different and bigger. And that something is the music of The Moody Blues.

Starting life in 1964 with vocalist Denny Laine, later of Wings, and bassist Clint Warwick the band found only limited success after their hit single, Go Now, and the 1965 album release The Magnificent Moodies, until the arrival of Justin Hayward, and bassist John Lodge in 1966, which heralded a new era for the band, and a complete change of direction from the white man plays R& B of their previous incarnation as they began the search for a sound which they could call their own.

Unable to get studio time without a hit single under their belt, and unable to get a hit single without studio time, the band moved to the town of Mouscron in Belgium, and began to write the songs that would form the backbone of their second album. They financed themselves by playing the club circuit, developing the harmonies that became their trademark, and learning to adapt to one another as musicians and writers.

In late 1967, the band were given their second chance when asked to go into the studio to record a symphonic rock version of Dvorak’s New World Symphony to demonstrate the newly created Deramic Stereo surround sound, in order to pay back their debts to recording giant Decca. The band however had other ideas, and saw this as an opportunity to put down on record their then current stage act, and demanded lockout time on the studio, giving them unfettered 24 hour access to the recording equipment. What came out of those sessions was the album Days of Future Passed, a fully orchestrated symphonic rock concept album, that explored one day in the life of Everyman.

Each of the tracks covers an aspect of our “hero’s” day; a musical reflection upon the sights, sounds and feelings that assault his senses, drawing us in until we are no longer just a listener, no longer a bystander, but are him, and he is us. The tracks are held together by instrumental bridges written by the conductor of the London Festival Orchestra, Peter Knight, who worked the themes and motifs of the band’s music and lyrics into linking orchestral pieces, in a lively and sometimes overblown style at times very reminiscent of Bernstein’s West Side Story.

The album opens with an instrumental, The Day Begins, before giving way to the dulcet tones of keyboard player Mike Pinder, and one of the two poems that bookend the album, and which had been hastily scribbled on the back of an opened out Players’ cigarette packet by drummer Graeme Edge, when it became clear that the piece needed a more formal and structured beginning and end.

Once off, the album proper is a swirling jaunt through a day in the life, from the almost childlike belief in the promise of a new dawn through to the embrace of yet another lonely night, with the entire band trying their hand at writing, and the vocals split mainly between new boys Justin and John, and old-timer Ray Thomas. It is this diversity of styles and talents that characterises the Moodies’ work, and it is a reflection of their abilities as singer/ songwriters that no one’s contribution feels lightweight or out of place on the album.

And so we get the nursery rhyme delights of Thomas’ Another Morning; the more out and out rock and roll of John Lodge’s Peak Hour which sounds like the Beatles scored by Brian Wilson, played by The Doors and sung by the Monkees jockeying for supremacy alongside Pinder’s nod to the East on The Sun Set, and the heart-tugging yearnings of wandering troubadour, Justin Hayward, on tracks like Tuesday Afternoon and Dawn is a Feeling. Twilight Time bounces us along with all the finesse of a pantomime horse in the desert and then of course there is the album’s, and The Moodies’ most famous track, Nights in White Satin which had to be dramatically cut for the 1967 single version, and was only re-released in its full length format to chart at no 2 in the USA and 9 in the UK in 1972.

Listening to the album today, you could perhaps find fault with some of the lyrics, which at times verge beyond the twee and descend into sentimentality, particularly the poems at its either end, which would have even old Mojo Morrison turning. In that respect, it is an album very much of its era, released in November 1967, (the month that also saw the release of Love’s seminal album, Forever Changes) with its oblique and not so oblique drug references, its sweeping orchestration and layered vocals.

And yet, the Moodies were always something more than a bandwagon band. Hayward’s folkier vocals and writing style, Thomas’ flute, pushed to the front, long before Anderson stood on one leg in his Peter Pan green, and Mike Pinder’s experimentation with the Mellotron, a cumbersome early synth that enabled the band to reproduce much of the orchestral sound of the album in their live ventures, set the band apart from their peers- with Days of Future Passed, a masterpiece of symphonic rock, the band created a legacy that spawned a generation of imitators who have perhaps never realized the debt they owed to 5 blokes and the mellotron taken from the Dunlop factory’s social club.

Words: Cold Ethyl