For me, and without in any way wishing to sidestep these narrative cornerstones, the charm of Jolly Lad (and for all the heavy stuff, it is a book filled with charm and that particular South Lancs/Scouse whimsy) is in its telling. It’s tricksy.

For me, and without in any way wishing to sidestep these narrative cornerstones, the charm of Jolly Lad (and for all the heavy stuff, it is a book filled with charm and that particular South Lancs/Scouse whimsy) is in its telling. It’s tricksy.

The other day I realised I couldn’t find Quietus editor John Doran’s new book. Then I remembered; I’d left it in the toilet, propped up against the porcelain base of the throne. The status toilet book in our house is an important one. It now fulfills the same duties as those titles in the revolving pile containing “popular” Ackroyds and Sinclairs, books I’m supposed to be reading for my studies, Cold Comfort Farm, Chrome Yellow, Head On and Japrocksampler (a real bowel loosener that one), Jonathan Coe’s biography of BS Johnson, Conspiracy Cinema, Brilliant Orange, Days in the Life, some old Rothman’s Football Annuals from the 70s, McClaren-Ross’s Memoirs of the 1940s and Kingsley Amis’s Memoirs. These books are there because their contents encourage rumination and some relief.

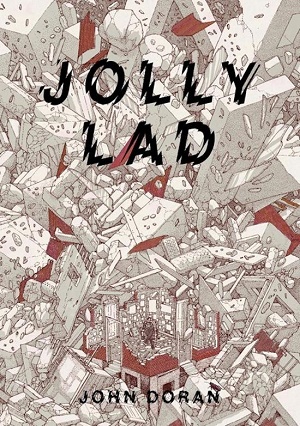

I think John Doran’s book has wormed its way into the earth closet pile because – despite reading it twice in a day – it’s not one I’ve been able to get the full jist of. It’s a tricksy book. On one level its contents are disarmingly simple. John talks about his life battling his demons, and making peace with himself and his environs. Simple as that. It’s a story of a lad from the provinces getting on after a series of ups and downs (as my Accrington gran would have it) and showing them lot from London where they can stick that pile of wood. Simple as that. On another, more “public” or “thematic” level it could be easily classified by those who haven’t read it as part of the canon of rock writer/rock thinker/thinking rocker popular autobiographies. I could point to 45, or Cider With Roadies. I won’t because Doran’s book is refreshingly of the sort of humblebrag/existential/weekend Pagan/”uomo universalis on the look out for a cash cow” balls that infects nigh on every tome in this field (outside of Cope’s truly great Head On/Repossessed). Other reviews, interviews or events that have accompanied Jolly Lad‘s release have focussed on Doran’s relationship with alcohol, drugs, and mental illness; including one intense interview round Alcoholics Anonymous. For me, and without in any way wishing to sidestep these narrative cornerstones, the charm of Jolly Lad (and for all the heavy stuff, it is a book filled with charm and that particular South Lancs/Scouse whimsy) is in its telling. It’s tricksy.

Because, for such a solid, Johnsonian figure, John Doran has a mysterious presence in his own story. Even though places and times are inked in in some detail, they still seem to be backdrops for a series of existential soliloquies that often lead to nowhere in particular. The more you read the book, with its tales of squat madness in Hull, Odyssean spirits, spice and powder stock ups in the Great Wen, or tales of subterranean Tubesick blues, the more you feel he is seen and not seen. I suppose that’s a fitting reflection for a book that chronicles a number of out of body experiences, dreams, nightmares. So; John Doran is here and not here in his book.

This hallucinatory quality often leads the reader astray; only for Doran to return to his point his devastating effectiveness. The last chapter, “Slaughter in the Air (2013)”, can be seen as a brilliant exercise in suggestion. Who is this “she” Doran talks about at the beginning? We can guess, but somehow Doran lets us drop the thread, and we imagine this reference to be just a casual, introductory aside. Doran then leads us away like some skillful master of ceremonies at a wedding; discussing his family history and roofing jobs with weed smoking ex-squaddies, only to reveal, almost in the style of a Grande Masque, the social change/destruction that that particular “she” initiated in his own neck of the woods. It’s akin to some MR James ghost story; the lulls, the reasoning, the relief before the unveiling; all the while the reader being slowly marinated on a spit.

Now and again you feel that Doran feels the need to play the game, and that’s where the book stumbles. That’s when he becomes like other rock writers. The rock journalist’s life is mostly spent on one’s arse, typing. Or it should be. Encounters with rock stars are for the most part mundane, or artificial, and sometimes weird, but not in a way that encourages reflection in print. No one needs to know anything more about Bobby Gillespie, for instance. However I must admit I laughed out loud when Doran told us how he and co-editor Luke Turner had managed to score a load of Mick Hucknall’s old clobber when moving the Quietus offices. His text encourages you to imagine the pair of them sitting there wearing Mick Hucknall’s stuff as if nothing strange had happened; maybe unwittingly striking the pose of the Ralf and Florian LP.

John Doran has become a very sensitive writer these last few years. I’m not suggesting that he’s gone soft, but he has an innate feel for the moral capacity of words. He understands that words can’t be chucked about willy nilly. In fact he is such a good writer, (one with wit enough to write about how best to tend your herbaceous borders, and the new Godspunk compilation), when I heard that he was going to base this book on his brilliant Menk columns written for Vice, I had misgivings. How would these brilliant essays translate as a narrative? But somehow they have morphed pretty well into the wider story; a messy, but winning struggle to keep your head together and do right by your family. And become, along the way, almost by accident (like Mr Benn popping into the shop for a quick trip to the Jurassic) a member of that most irrelevant (and increasingly ossified) of professions; the rock writer. In London, too. Oooh, think of that. That, in itself is quietly heroic.

Postscript: The book’s core dreaminess is fully explored (albeit in a different medium) in the CD. The CD is, to nab a Scouse phrase, boss. Really boss, and deserves a review for itself, not this footnote as in many ways it’s a separate entity, expanding on, and sometimes giving real substance to, Doran’s reflections. Everything on it is brilliant; for instance the Bronze Teeth track, Hypnotherapy; a juddering rumbling halftrack careering through scrub. Doran’s voice, a very nice, reassuring voice (a voice MADE for radio) leads us on, sounding like a stoned porter explaining the membership rules at some naughty Victorian Soho club. Well worth tuning in.