"The truth is in the Music. Who turned on the bright lights? – One man’s quest to find Interpol", by Jonathan Dekel.

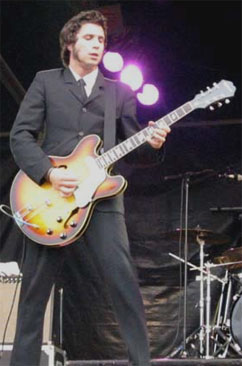

Photo by Nathalie

Its mid-march 2003, I’m on a train from Amsterdam to Brussels with a friend of mine who I’ve just picked up from the airport. Somewhere along the way we start talking about music, as you do, and he looks in his bag and hands me a record, "Man, have you ever heard of this band, Interpol?" I had, but what I’d heard didn’t do anything for me and I told my friend so. I explained to him at some length that I was always wary of bands that appeared from within a gigantic hype cloud and Interpol’s hyperbole storm machine was working overtime at that point. They were of the new wave of bands from New York [this wave would also include the Yeah Yeah Yeahs] and I’d already staked my claim with The Strokes and The White Stripes as the saviors of rock. I thought I don’t need another garage rock band to save me; I’d already been saved. My friend smiled one of those smug smiles people get when they know something you don’t, leant forward and offered his walkman to me, saying "Have you heard the album?" The answer this time was a polite no. I took the walkman and prepared myself to be disappointed, if only to wipe the smug look off my friend’s face.

As soon as I put on the earphones however, the music I was listening to instantly struck me as clear, effortless, serene, and beautiful. This was not the down and dirty New York band I was expecting. An emotional downpour of fluid guitars, mathematical bass lines, and otherworldly drum signatures took over, gently careened by a voice so apathetic and emotional; a voice that had not been heard since, lets face it, Ian Curtis. But that’s where the comparison ended, the critics had it wrong (now there’s a surprise) this band weren’t the new Joy Division, they were more than that. Where Joy Division let their lack of musicality be overrun by the determination and heart that went into their songs, Interpol were almost prog-like in their timing and playing abilities. As the last notes of NYC faded from my earphones (only three tracks in!), I turned to my friend and told him that one-day, come hell or high water, I would meet this band. In May 2003, I made it happen.

By now, I was firmly clued up as to who Interpol were. I knew well their faces and suits. I knew all about they style over substance mantra which they constantly deny, yet refuse to change. Incendiary was still in its early stages when I found out the band would be playing the Melkweg around our intended launch date. For days I swapped e-mails with their press person, trying to secure an interview with the band, even promising a cover story, but it was to no avail. I was left with the promise of an interview next time they come around.

Not easily deterred, I went to the concert determined to get the interview one way or another. I stood stage right, mouth open, in awe of the four knights in black suits parading about on stage. Gallantly swinging their instruments in perfect measure, they stopped only to thank the audience briefly and politely. It was the mystique I suspected, and hoped, they would bring with them. As the concert ended, I knew it was time to make my charge. A couple of words with the bouncer and I was backstage, in the dressing room.

The first person I noticed was Carlos Dengler, the band’s mammoth vampire-like bass player bouncing around the room yelling and screaming excitedly. Eventually he settled on a couch, flanked by two girls vying for his attention. Sitting quietly to the right of one of the girls was Eric, the band’s live keyboard player. Paul Banks, the lead singer, stood in the back of the room. In keeping with his on stage persona of looking cool but saying little, he just stood, calmly drinking his beer, taking the whole scene in. Finally there was Daniel Kessler, the band’s guitarist. Sitting at the table eating, he looked like the one member of the band in touch with his surroundings, that is to say he was the only member who didn’t appear to be on something (A suspicion that was later confirmed to be true). As for Sam Fogarino, the drummer, well, he was nowhere to be found. I stood at the door, casually trying to figure out how to approach the band, or at least to make eye contact and decided I’d try Carlos, who seemed the most talkative.

My tactic proved successful as three hours later I found myself at the Paradiso, appointed by Carlos to watch over him because he was ‘a people person’ [especially when he was out of his face on E]. I played chaperone for a while but left him soon after with a black haired girl of his choosing. She seemed to be taking care of him just fine anyway. Paul had gone back to the band’s tour bus complaining he didn’t feel well, [it turned out he was coming down off a mushroom trip – for confirmation see the band’s touring diary in American mag, Spin]. Eric was sitting downstairs chatting up a girl and casually taking swigs of Jameson from his flask. This left Daniel and I upstairs in the balcony, watching over the collective pulse of the dancing.

Flash forward about four months. I’m backstage at Rotterdam’s Metropolis festival. Staying good on my own promise, I am scheduled for an (official) interview with Interpol. Having confirmed it three days earlier from a phone booth in Rome with a slightly bewildered press agent I arrived at the venue and inquired as to where the band’s tent was and found myself talking to Martin, the very same bewildered press agent who greeted me with a big smile. As I chatted away, explaining the complexities of this here Incendiary institution all I could think about was that train journey and then a few short minutes later, I found myself at the tent where Daniel was seated, playing with his laptop and editing a song, wearing the same sleek suit as the first time I saw him. Noticing my entrance he closed the laptop, preparing himself for the interview.I sat down, put the recorder on the table, and began:

You guys had a following in the UK even before this current hype; you even had a Peel session. How did that come about?

The Peel session wasn’t even about hype. I mean after we did it, we made some more fans but we were just lucky enough that John Peel liked the EP we put out on Chemical Underground, and he’d been spinning it. We wanted to go over to the UK and do our own tour, and with the help of Chemical Underground, who lent us a lot of the equipment, we self financed the tour of the UK. That didn’t really start the hype so much. We made some new fans, or some initial fans, but we really didn’t get that much attention, honestly, till we put out the record. We did our first proper single after the Chemical Underground single, in May 2002 and the album came out in late August. It wasn’t till the album came out that people started paying attention, which is kind of the ideal way for it to happen for us. Just from people hearing the music and not from people hearing that we’re good or something like that.

Tell me a bit about your crossover from Chemikal Underground to Matador.

We never actually signed to Chemical Underground, it was always very obvious to them and us that we were just doing an EP. It was part of a series that they put out. They’ve been fans of ours, and very supportive of us since almost the very beginning, and Matador was just one of our favorite labels, certainly one of mine. We were sending out demos to everyone, trying to get their attention and we sent it to Matador. We kept in correspondence with them, they really liked the Peel session we did and some self-recorded demos and they invited us down. We got along well, and y’know, voila!

Why do you think your songs have struck such a chord with UK audiences over everywhere else?

Actually, I find we have a much bigger fan-base in North America over the UK. I mean, in the UK we do well, but European audiences haven’t responded to us as well as American audiences.

Why do you think that is?

I don’t know. I think we’ve struck a chord with audiences and its not divided by countries, I think there’s something in our music that hits people a certain way maybe its something other bands weren’t doing, I dunno. But people seem pretty attached, and people responded quite well after we put out the record. There was a great word of mouth that spread out, and it happened in a very similar way in America as it did in Europe.

Are you annoyed that most of the major media on both sides keeps comparing you to Joy Division?

At this point yeah, I mean it’s a bit trite. Our responses are well documented everywhere we go. I mean people can think whatever they want, but ultimately, everyone knows how we feel about it, or they should. If they want, there are plenty of sources out there to look at.

Getting back to the UK, both you and Paul grew up in England; Do you feel a special attachment to it?

I mean my mom’s English, so yeah. Wherever you’re born you feel a certain amount of attachment to. But I’m not overly nationalistic or attached to it. I mean my brother still lives there, my mother’s English, my godmother’s English. Both Paul’s parents are English and they both reside there. I think we both feel an attachment to England, but I think we both feel an attachment to other places too, so.

Do you think that factors into your music?

No, I mean I think being born there was an interesting time. I was born in the seventies and I remember The Jam getting big when I was really young and my brother liking them, but I don’t think it factors into the way we play, no.

You guys have been playing several new songs on the tour, two or three a night as I’m to understand it…

At most two a night, and alternating.

Any names?

One of them is called ‘Length Of Love’, and other one doesn’t have a title yet.

When do you think you guys are going to record the next album?

We’re touring straight through till the middle of November so we’ll need a few months after that to work on some new songs, so probably not till spring or sometime after that, spring 2004 probably

Getting back tot eh current album, what does PDA stand for?

There are many definitions for it. One is the obvious, public display of affection, I don’t know if it really stands for that though. A lot of our song titles are more from moments and less from the chorus. For me, I remember when we came up with the title PDA is was loose. I think it makes sense for the lyrics, but loose as far as why we came up with that title.

Rumour has it that Turn On The Bright Lights is a reference to the 9/11 memorial, but I assume that’s not true?

[laughs] no, I mean we wrote NYC in January 2001, and we recorded it for John Peel in April 2001. So no, it’s absolutely not from that.

A lot of people say that New York has changed since the attacks; do you still feel the record is still relevant?

I think a lot of things have changed. When we wrote NYC, there were no songs that we knew of that dealt with New York City subject matter like that, but obviously since then all these New York bands have blown up, and obviously since 9/11 things have changed. I mean, the meaning has changed a little bit, but I feel its still a pretty accurate description, or a possible description of New York City in a moment in someone’s life. So in a way I don’t think its changed or the meaning’s changed because New York City is still the same New York City that the song embodies. Every day it can be one way or the other in New York City, and that’s just one way of looking at it, y’know?

Speaking of New York, you guys are on a new compilation called Yes New York, how did that come about?

Chris White, the manager of Radio 4, who books the CMJ festival in New York, he wanted to do a compilation of all these New York city bands, and it’s a benefit as well. They just invited us and we were on tour so I haven’t actually seen it, but we know he people who produced it quite well so when they called, we said ‘yeah.’

Why do you think the New York scene has blown up now?

I dunno, I think right now its because the media has been paying a lot of attention to it, and fortunately there’s a lot of good bands to back it up. But maybe if you paid attention to Tuscan, Arizona, there’d be a lot of great bands popping up there, or given the opportunity there may have been some great bands in New York five years ago, you never know. Its hard to say how much of it is the media giving people a chance, and how much of it is a really great scene in New York. I’m weary of ‘scenes’, I don’t really care, It’s not important to me. Good music is important to me, not where it comes from.

Photo by Nathalie

As he said those final words he looked me straight in the eye, almost egging me to go on and challenge him. However, it was not meant to be as the band’s manager came in to stop the interview and request that Daniel rejoin the band as they continued doing their pre-show rituals. As we shook hands, there seemed an unsettling familiarity which is uncommon among interviewers and interviewees. Kessler, and Interpol as a whole, are the exact opposite of their music. Whereas the music is unbending and repetitive yet predicable and warm, the band themselves are anything but, often unstable and yet constant in their ability to show it and survive.

As I walked out of the tent and was met by the same black haired temptress I left Carlos with the last time, a certain familiarity swept over me. Interpol are no longer this hype-machine, but rather a band, unto their own. One with so much potential, one can only hope they livelong enough to truly realize it, and perhaps, if not change the world, at least keep conquering it. One fan at a time.