“When you start to age now, you begin to think you’re lucky.”

“When you start to age now, you begin to think you’re lucky.”

http://www.louderthanwar.com http://www.themembranes.co.uk

Yeah. John Robb says that a lot: yeah. A reaffirming ‘yeah’, one that only comes at a certain age, with a certain level of understanding on how words and language can become a natural extension of yourself.

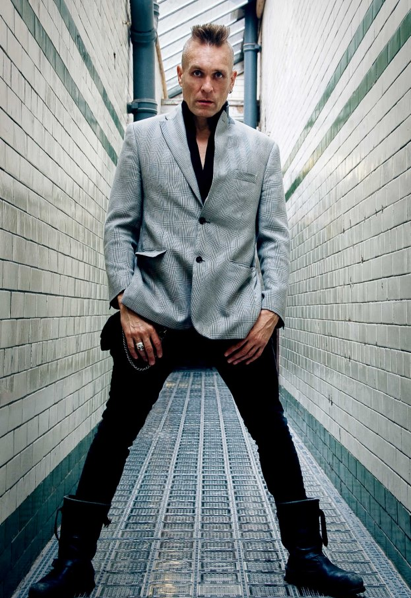

There’s always a sense about Robb that somehow he instinctively knew the importance of DIY-culture as a self-assertive 19-year old punk kid from Blackpool. Now a 53-year old chief editor and owner of music and culture e-zine Louder Than War, his tireless, almost evangelistic testimony to punk culture is as well-rehearsed as ever.

Unlike most rock pundits, Robb wasn’t satisfied watching punk’s outbreak play out from the sidelines. He dived headfirst into it, consumed it, acted it out and became a vital part of it. His own band The Membranes became yet another footnote within the punk rock canon, and its idea of creating a culture with its own rulebook and artistic statements. His idea of punk rock is not just propelled by an insubordination towards settled life, but towards its contemporaries as well.

In May, the recently reformed The Membranes are set to release their first album in nearly two decades, Dark Matter/Dark Energy. Last summer, Robb was kind enough to speak to us prior to The Membranes’ gig at WORM, Rotterdam.

Funny how The Membranes consider a nineteen-years break, you know, a break. Instead of having people assume you’ve broken up. Wikipedia seems to think so, anyway.

We just thought we’d take a couple of day off, and nineteen years went past. [Laughs] The last gig we played before our breakup was in ULU in London, with Inspiral Carpets I think. At that point of time, that kind of noisy distorted music was completely dead in the water. Nobody was all that interested. The weird thing is, the last few years people have become really interested. But we don’t actually play all that often. When we do, we just perform lots of new stuff instead. The idea of The Membranes was to never be a retro band that goes around playing old songs. It’s easy for us to do that, because we don’t actually have any hits. [Laughs] So, it’s an attitude, like punk’s an attitude, isn’t it? There is no specific sound, it’s an idea really. What The Membranes do, it’s simply our idea of punk.

When you place yourself into a new zeitgeist after two decades, especially being so up to speed on music as a critic, did you have to scrutinize at first: are we going to adapt like a chameleon or do we still somewhat enforce the aesthetics that initially made our music singular? If so, where did you balance that?

You tell me whether we should bring that aesthetic… Well, because we’re older we’re simply a different version of that aesthetic. The original aesthetic of The Membranes… [Pauses] When I talk about a punk band, it’s doesn’t sound like a conventional punk band. When initially I got into punk in ’77 there was no ‘punk sound’. You can go from The Stranglers to XTC to The Sound, Suicide, The Clash or The Sex Pistols. It was all different. And it got narrowed down to a template punk sound, which I like as well. Goldblade is more of a celebration of that template-sound, while The Membranes have always been a reaction to it. Which is – when you strip things down to its essence – very much within the punk spirit, actually. As far as the new Membranes-material’s concerned, nothing’s out of the question. We apply strings, choirs anything that sounds good, really. Nobody’s saying you’re allowed to have that, because that’s not the ‘punk’ thing to do. We’d act pure on instinct, if it felt right we’d go there. If a song’s nine minutes long, or thirty seconds, we’d do it. There are no rules, you know…that’s what’s great about it.

Those earlier Membranes-records where really schizo in that sense, at the root of all those sounds. From Beefheart, The Stranglers to Suicide to the earlier punk stuff.

Yeah, a continuation of that spirit, that’s what it is. We can’t play the whole Led Zeppelin songbook, but we can play our own style of music better now. That kind of lo-fi charm is fantastic, but it gets a little bit ridiculous when you get in your fifties. You should’ve learnt a few more tricks by then, yeah…

You said in your TED Talk that the impetus to say what’s on your mind becomes stronger as you get older. What’s difference between maintaining that candor as a 19-year old punk from Blackpool and as a 53-year old rock critic/musician from Manchester?

You definitely think you’re nineteen forever to say stuff, but when you get to 53 you see the finishing line. You definitely feel the end. Friends, people you knew have died on the way here. When you start to age now, you begin to think you’re lucky. Its a time when you slow down, get some stuff and create room for other stuff. You don’t burn out, because your creativity doesn’t stop. It actually shines now, because you’re not in a rush anymore. I always say there’s no point in adjusting, you don’t have to fit in anymore. You’re just doing what you’re doing, at this age. There is no idea that you have to be part of anything. It doesn’t matter anymore, does it? You can be unapologetic about it now. It’s a work of art, you put it up on the wall. If no fucker wants to look at it, no matter. Just make another one. Yeah. It doesn’t kill me. If you make a record that’s yours, the most perfect record you ever made.

Punk is often seen as this antagonistic culture, but you put it in this really positive, almost evangelistic light.

It’s a positive thing though isn’t it, when you see the finish line it makes you more positive doesn’t it? It makes you realize there’s a reason for it. It’s not a hobby, is it? It’s completely everything in the world. You fuck up everything in your life to make these things work. You don’t own up to anybody, and you can actually get a pretty good job if you venture out into ‘the real world’. But this…This has to be done. It’s more than a vocation. The intensity of it, it’s everything. That was the point of those TED Talks. The idea that punk rock is a DIY culture, where you can do everything yourself. I’m not knocking Green Day, because they’re a very good pop band. Whomever says they’re sellouts, that’s bullshit. It would be a sellout if they were trying to sell out Shellac. Green Day doesn’t sound like that, they naturally write good pop songs. That’s great. But almost feels like an alien world when I go see their gigs at stadiums. It’s so big and far off from the idea of punk rock as a DIY-culture. Maybe that’s one end of it, the other end of it, the idea of punk rock culture where you can do as you please, the message is so true that you can actually create your own culture. You don’t take up the culture and let it dictate you. You don’t want to be on MTV, you want to make your own culture. Green Day started like that, they played Gilman Street, a famed DIY venue in the US. They were the house band there, they played there twenty six times. They played there loads didn’t they? They sell their records and write songs, political songs even. That’s important, but shouldn’t be just that thing where just play gigs and sell albums and t-shirts for 18 pounds apiece and that’s it, that’s your punk statement. You should be creating your own stuff. It’s not necessarily just the music. You can set up your own website, set up something social or political, something crazy. It’s a proactive, catalytic thing, doing something that makes the world a bit better. You should see a performer, get energy from that do something positive with it.

When was the last time you saw this rift of counter-culture in mainstream music?

It’s always there. It’s the eternal battle between the mavericks and the corporates trying to control everything. As soon as they put up a new wall, they throw paint on it. I love it, those little tears in the fabric of life. They build these squares in Manchester, you have these office workers sitting there painting a picture of what they want it to look like, drinking expensive wine. Yet within a week there’s kids skateboarding. They don’t want those people there. That’s victory isn’t it? It’s those tiny things. Just fuck up their idea of what the perfect world should be. Some of these modern buildings are really good, you know? I was just admiring the new station in Rotterdam, it’s actually a really beautiful building. But that’s because it’s built for people to go by train, unlike these eighty-five story towers built for banks and security guards patrolling around. I like shared spaces. I like to share culture, communities. That what I do with Goldblade and Membranes, we just put on some racket in a room where everyone is jumping up and down. There are no stars, everyone should feel equally important. It’s like that Was (Not Was) song. isn’t it: “When the woodwork squeaks, out come the freaks.” When that tear the fabric happens, a tidal wave got through. Everytime a punk band played Top Of The Tops back in the seventies, I’d be like: “One of ours got through.” They couldn’t stop it, could they? I like those kind of moments. And maybe it’s building up to a moment like that again. I just don’t understand why punk rock music has to be elitist. Why do we have to keep it in the underground?

It’s exciting there are still bands like Fat White Family and Sleaford Mods representing the counter-culture. Because ever since the term alternative music came to be, it became more and more compartmentalized. The indie thing was kind of the straw that broke the camel’s back, wasn’t it?

Indie has become a marketing term now. Coldplay are kind of U2 aren’t they, it makes sense that Coldplay found inspiration in indie music culture like U2 did. But after the recognition, it gets sold as a lifestyle choice on high street.

Which leads to Ramones, Joy Division and Nirvana-merch being sold by popular retailers.

I was walking through Barcelona about ten years ago, and they were selling punk clothes at this posh supermarket. Someone spray painted on the window: get your hands off our fucking culture. I thought that was brilliant. That culture isn’t exclusive, it belongs to everybody. I don’t like it being sold back to people. If you want those clothes, make them yourself. Or go buy them off someone in the underground, to keep that going. There’s nothing wrong with making money, but in the worse case scenario capitalism becomes this juggernaut that bulldozes everyone down. It’s inherently contradictory too, because we’re all sitting around complaining about it on our computers. [laughs] We’re all buying into it. If my friends could make a laptop out of a piece of wood, I’d buy it from them. But I can’t, so we’re all hypocrites in the end.

How did you embrace DIY-culture in the beginning? Did it feel important from the start?

It just affected a few people very strongly. Blackpool is not a ‘hit’ town at all. It’s a seaside town, a big one… But stuck in the middle of nowhere. It’s a bit risky, people would punch you in the face. Back then I didn’t look much like a punk, I just had long hair and flares on, that was enough to look weird then. The whole package of it was brilliant, the politics, the zines, the clothes, the music, the stands. As soon as you heard it, it just struck a nerve. I got consumed by it really. But we didn’t know what the rules were. We were small town, we didn’t really realize what it really meant. So we just went out to Oxfam, to some second hand pawn shop. I didn’t know the Pistols had a woman on the road making their clothes for them. Big show business. We just couldn’t get that stuff up North. We used to get these 50’s suit jackets from second hand shops, and just wear those. You’d had to get all the way to Manchester by train to get black trousers. Getting records was hard, it was a quest. It would take a months to get good underground records. Now it’s YouTube, SoundCloud and Spotify and you can get a whole album. I love the whole idea of that as well. The quest is four seconds now.

Often times it feels like being stuck in a cash cube. Fifteen years ago when Napster happened, you found yourself affixed to your computer screen, slowly watching percentages creep up. It could take five minutes, or it could take a full hour, but eventually you had a song in all its 128kbps-glory.

I love the nostalgic talk about Napster, that just tells me punk culture keeps moving. When Napster came up, people were worried as fuck, because no one’s buying records. It’s great to have to wait two weeks to buy a record. I like the way you talk about that hour. In twenty years, people might find four seconds a ridiculous amount of time to discover new music. [Laughs]

I find it fascinating how this era of connectivity can produce something as cross-cultural as Caïro Liberation Front. It’s special to see something like that blow up, become this global thing.

Yeah, saw them in Tilburg, they’re fantastic. I’ve always had this theory that punk music in the seventies is nothing more than English folk music. Chaabi is like the Egyptian folk music of now. It’s wedding music, they play it after a party in the wedding with a thousand kids dancing in the streets. It’s same kind of music that they make themselves. FOR themselves. It can only reflect the place you’re from, right? So when we made punk music, it’s our reflection of growing up in the North of Blackpool. It wasn’t a copy of The Ramones or The Pistols. It wasn’t London or New York, it was ours and it was different. When I see these young kids doing Electro Chaabi, it’s very much Egyptian punk. Yeah…

I’ve heard people calling their act patronizing, but I beg to differ. I think them integrating Western sounds actually gives it more validity. That’s how things unshackle, how to break new ground.

I love so-called ‘world music’ but I hate it when people say you need to play traditional instruments. They always go: “Why are they using samples? That spoils it!” Ridiculous, why can’t they use modern samplers? Why can’t we have a DJ on a turntable and a kid doing an Egyptian style melody. It’s no different from that culture. It’s the same kind of mentality and they’re coming out on their own. It’s not tidied up, it’s still loose. It’s a modern world isn’t it? There was a time, when you wanted to hear Egyptian music, you had to go to an Egyptian record store and even then you wouldn’t even know what you’re buying.

It’s not that different from a band like The Soft Moon drawing from music like Section 25, perhaps a bit more radical maybe.

What a great underrated band that was. Equal of Joy Division. Because they didn’t have a charismatic singer who died young they were written out of the whole narrative. They sound more modern now. A lot of those hipster bands are just catching up to Section 25.

Why exactly did you want to play bass instead of guitar in The Membranes?

The Stranglers really. They wrote pop songs, but they were a pretty weird, awkward band. But very intelligent. They were the biggest band after The Pistols at one point. Anyone my age played the bass because Jean-Jacques Burnel is the best bass player of all time. Incredible bass player. Best bass sound. Best bass lines. Cool as fuck. I didn’t know what bass was before I heard The Stranglers. At first I played guitar and in Goldblade I just sing. But with The Membranes I play bass. Post-punk music is all about bass anyway, it’s all about equal instruments. When we talk about the airport in Amsterdam, Schiphol. Best airport in the world isn’t it? The station is actually inside the airport. Everywhere else you have to travel three miles to reach the next town. It’s built like the concept of Dutch football, with everybody is running around all the time. And everybody plays the lead for some time. That sums The Membranes and post-punk music in general really well. When I listen to Shellac now, I hear what we did in 1987. I know Steve Albini was a big Membranes-fan. He had our records, our fanzines. He learnt to play that style absolutely brilliantly, made it super technical. We had the sound and ideas, but we were so rudimentary in our playing we could not execute it perfectly. Albini on the other hand, had enough money to run a studio. I didn’t know any bands that owned a studio at the time. It was the finest, most perfect extension of what we were trying to do at that point.

Going back to your commentary before on punk being a proactive, catalytic concept, something more than just music-related: what are your thoughts about Pussy Riot getting arrested? It was the first time in decades that a small independent punk movement managed to shake things up on a global scale.

There’s a lot of very interesting angles on this. First of all, I think they’re fucking brave. You find me one Russian politician on their side. You won’t find one. In Russia, even the liberals don’t like them. That was odd, because they are fighting for the same cause. The other thing was, Louder Than War was actually one of the first websites outside of Russia that covered Pussy Riot. Then some friends and MPs picked up on the story and it percolated in England from that point. I actually knew their manager at a music conference in Estonia from way back. Anyway, most people in Russia don’t like Pussy Riot because they haven’t been told the truth about them. Most people think they went to one of the holiest churches in Russia, but it was only built there years ago, it was a new church. They think Pussy Riot attacked an old lady there, did this song to desecrate the altar. What they don’t realize is, that it was just ten seconds of noise. That’s all it was. They didn’t actually damage anything, did they? There’s a lot of editing of the truth going on. I actually met them in Estonia, I did my little instagram picture with them. [Laughs] I didn’t realize they could speak English, but I like it when they just speak Russian when they answered questions. The thing is, Pussy Riot are not anti-Russian, they are very touchy about that. You’ve got to understand from a historic standpoint, Russia won the second World War. They broke the back of the Nazis yet they didn’t get the credit for it, did they? The battle of Stalingrad had over three million casualties. I went to St. Petersburg once and they showed us the line where the Germans couldn’t cross any further. This is a very important point, because the way we get told about the war is that Russia’s part in it gets missed out. So there is this big cultural gap there. What they know is that the people over here don’t know that part of history. So there’s been a continued misunderstanding from that point on between Europe and Russia. But the misunderstanding about Pussy Riot is that they’re preaching anti-Russia. They’re anti-Putin, which is a different thing. So you could take their speech to an American court and it’ll still hold true there. A lot of people will come and used them as pawns, but they refuse to be used. And the idea they’re women is important as well, because within the macho culture people don’t like the idea of women answering back. That’s not something that goes over well in Russia. It’s kind of the same over here you know, we’re not the liberals we think we are.

I’m kind of surprised about the notion that Pussy Riot are so universally disliked in Russia. In the documentary I saw some pretty Orwellian imagery. Perhaps it’s just smoke and mirrors we only see in front of cameras, who knows? But the coloured balaclava was used there in a likewise emblematic context as the Guy Fawkes-mask.

Yeah, there is a minority of people support them, of course. But quite a few liberal people I know don’t. [pauses] But things change don’t they? In years time Pussy Riot might start to get their due. When The Sex Pistols became big, Johnny Rotten got his face slashed walking down the street. Years later you can buy a baby bin with a Sex Pistols logo on it there. It just becomes picture postcard-history. It could be that the Kremlin will sell Pussy Riot-balaclavas in all the souvenir shops. [laughs] It becomes toothless when it’s just another trinket to buy, doesn’t it?